Dropping blood pressure to 120 lowers heart woes, data confirm

SPRINT study results support new, lower target, but also reveal risks of aggressive treatment

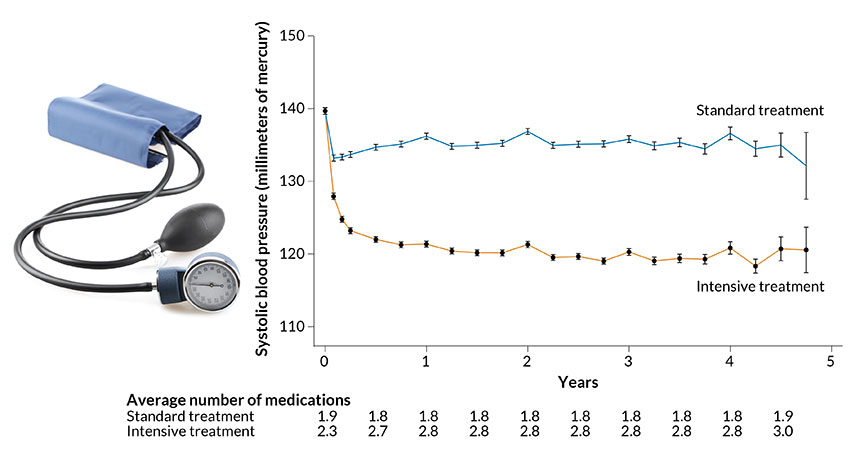

UNDER PRESSURE Hitting a systolic blood pressure target of 120 millimeters of mercury took, on average, three drugs for a group of participants undergoing intensive treatment (orange line) in an NIH-sponsored clinical trial. To meet a target of 140, another group of participants (blue line) required, on average, two drugs.

fotohunter/Shutterstock; graph: J.T. Wright et al/NEJM 2015