MAVEN mission finding clues to Mars’ climate change

Orbiter collects clues about how the sun is stripping away the Red Planet’s atmosphere

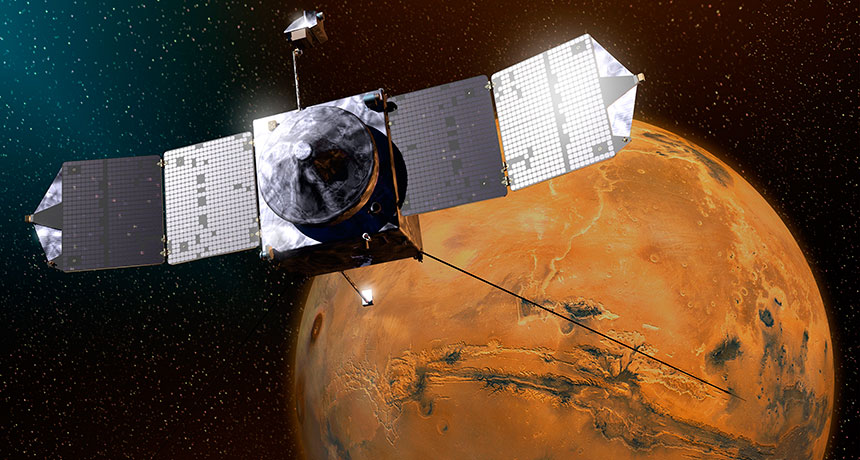

SOLAR ATTACK After over a year of orbiting Mars, the MAVEN spacecraft (illustrated) finds that energetic particles from the sun played a major role in robbing the Red Planet of its water.

NASA

- More than 2 years ago

Solar winds slowly chip away at the Martian atmosphere while flares trigger widespread auroras. These are just two findings from MAVEN, NASA’s most recent mission to Mars, that appear in four papers published in the Nov. 6 Science.

By now, it’s clear that water once rushed through canyons and filled basins on the Red Planet, but not anymore. Whether the water escaped into space or was sequestered underground, understanding what became of the H2O can help researchers better understand the ancient Martian climate and its past habitability. After roughly a year of orbiting Mars (SN Online: 9/22/14), the MAVEN spacecraft is providing some important clues.

“Loss to space was a significant, if not dominant, process in changing the climate,” says MAVEN principal investigator Bruce Jakosky, a planetary scientist at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Thanks to the steady stream of particles and plasma from the sun, Mars currently loses about 100 grams of its atmosphere every second, researchers found. That may not sound like much, says Jakosky, who coauthors all four papers. “But over a couple billion years, it can remove an amount equivalent to today’s [Martian] atmosphere.”

Other orbiters, such as the European Space Agency’s Mars Express, have seen hints of atmospheric escape, but not at this level of detail. “This is a fantastic result,” says Dmitri Titov, project scientist for Mars Express and a planetary scientist at the European Space Research and Technology Centre in Noordwijk, the Netherlands. “Until now, we had only models and a couple of measurements with spacecraft.”

While the sun steadily erodes Mars’ atmosphere, solar flares can take out relatively big chunks. After a flare in March, MAVEN noticed that the number of ions streaming from the planet jumped by roughly a factor of 10. Such flares were probably more common and more intense in the past when the sun was younger and feistier, Jakosky notes, and might have sloughed off much of Mars’ atmosphere.

“Solar history is the big elephant in the room,” says coauthor Janet Luhmann, a space physicist at the University of California, Berkeley. “If this is going on regularly and much more vigorously in the first 1 [billion] to 2 billion years of solar system history … then we have to take that into account.”

Atmospheric light displays that blanket Mars’ northern hemisphere, first reported in March (SN: 4/18/15, p. 15), provide another clue that energetic particles from the sun dump energy deep into the Martian sky, notes Luhmann. Because Mars doesn’t have a global magnetic field like Earth does, it can’t protect itself from the onslaught of electrons that threaten to strip off its atmosphere.

As MAVEN dove in and out of the upper atmosphere, the probe also recorded surprising variability of ion abundances, which provides some hints at how the different atmospheric layers interact with one another. And previously reported dust particles swirling around the planet (SN: 4/18/15, p. 15) are probably swept up from interplanetary space, and not lofted up from the surface or sprinkled down from Mars’ two moons.

MAVEN is about to start an extended mission, which will let researchers see how the leaking atmosphere responds to the changing Martian seasons, each roughly six Earth months long. If funding allows, the spacecraft has enough fuel to hang around Mars through an entire 11-year solar cycle, Jakosky says.

Streams of oxygen ions escape the Martian atmosphere in this computer simulation. The highest energy ions (red) are funneled over Mars while lower energy ions (green) form a tail pointing away from the sun. NASA Scientific Visualization Studio, MAVEN Science Team |