Vampire microbes sucked some ancient life dry

Punctures in 750-million-year-old eukaryote fossils suggest predation drove self-defense evolution

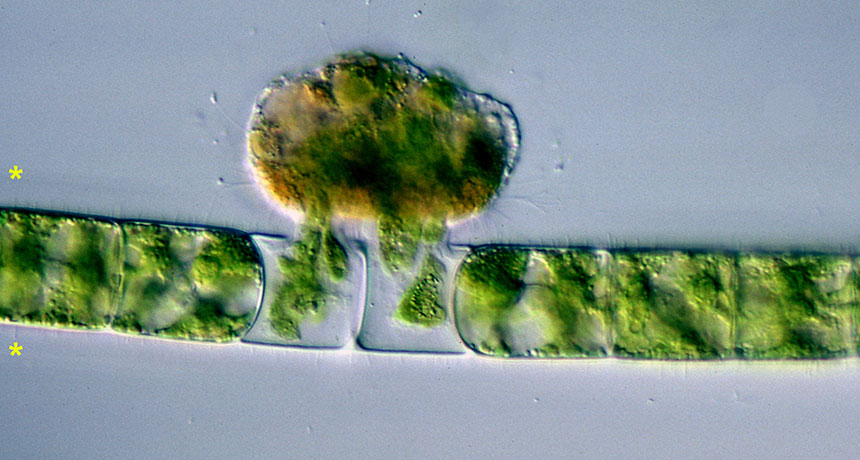

VAMPIRE DIARIES Fossils from around 750 million years ago show evidence of vampirelike predation similar to that of the modern Vampyrella ulothrichis, shown here eating the innards of green algae.

Norbert Hülsmann/Flickr (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

- More than 2 years ago

BALTIMORE — Microscopic vampires may have prowled the ancient seas around 750 million years ago. The fossilized remains of their punctured victims may be the oldest direct evidence of predators hunting eukaryotes, a domain of complex organisms that includes plants and animals.

While the monstrous microbes probably didn’t look like miniature Count Draculas, “they’re just as terrifying, at least if you’re a single-celled organism,” said paleontologist Susannah Porter of the University of California, Santa Barbara November 1 at the Geological Society of America’s annual meeting.

The predators perforated holes in their prey and then slurped the victim’s juicy innards, Porter proposed. This predation helped drive single- and multicelled eukaryotes to evolve innovations such as skeletons and the ability to burrow as they fought to survive, Porter suggested.

The early emergence of predation makes sense, says Paul Falkowski, an earth systems scientist at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J. “Once you make an organism, somebody else will figure out a way to utilize its juices.”

Eukaryotes first appear in the fossil record around 1.8 billion years ago, but they didn’t start rapidly diversifying until around a billion years later (SN: 11/14/15, p. 18). The emergence of predators probably helped spark this burst of eukaryotic evolution, but identifying behavior such as predation in the fossil record is tricky.

As Porter examined 750-million-year old eukaryotic fossils from the Grand Canyon using a scanning electron microscope, she noticed something odd: Several fossils had clean-cut circular holes in their cell walls, with several specimens containing 30 or more punctures.

While hole-riddled fossils are nothing new, the wounds seemed deliberate, Porter said. The perforations ranged in size from 0.2 to 2.9 micrometers in diameter (the thickness of a red blood cell falls within that range), but the holes in any one fossil were always roughly the same size. Some holes were even beveled, with the gaps narrowing toward the fossil’s interior. This evidence points to predation, Porter said, rather than other processes such as mineral growth that can poke holes in fossils. Fossils of the predators themselves have yet to be found.

Several modern microbe species exhibit similar hole-punching behavior, including the aptly named Vampyrella group of predatory amoebas. Scientists think these marauding microbes use enzymes to eat away a hole in a victim’s cell wall before extracting the cell’s contents or even slipping through the opening to eat the cell from the inside out.

With vampirelike predators haunting the seas 750 million years ago, any one eukaryote species would have had trouble maintaining dominance, Porter said. The presence of predators maintains high diversity and encourages organisms to develop new ways to avoid getting noshed.

A predation-sparked arms race probably led to some eukaryotes donning scalelike armor for defense, an innovation seen around this time in the fossil record. “It’s stupid to make armor unless you’re defending against a predator,” Falkowski says. “Organisms that have no predation pressure will just have very simple membranes facing the outside world.”

Porter agrees: “Predation is such a strong selective pressure — you don’t want to die.”