Itch-busting nerve cells could block urge to scratch

Mice studies show how brain deals with irritation of light touch on hairy skin

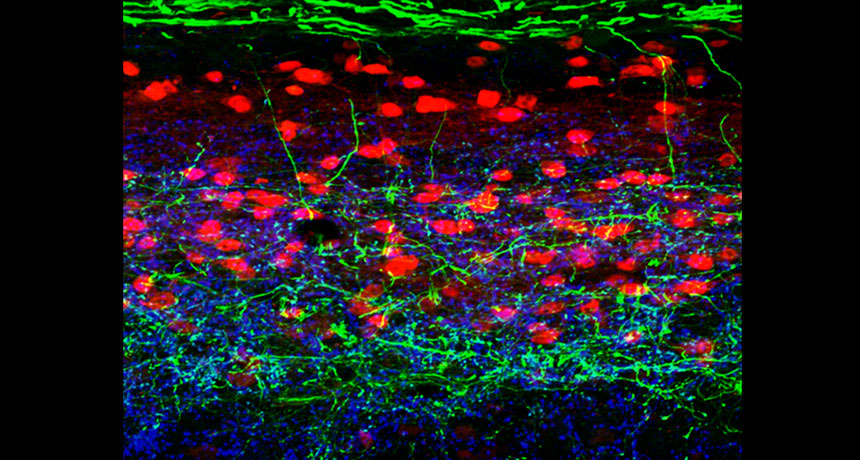

UP TO SCRATCH A group of nerve cells in the spinal cord of a mouse (red) curb mechanical itch, a new study suggests.

Salk Institute