Hepatitis E vaccine shows strong coverage

Large trial in China indicates 87 percent protection against the virus

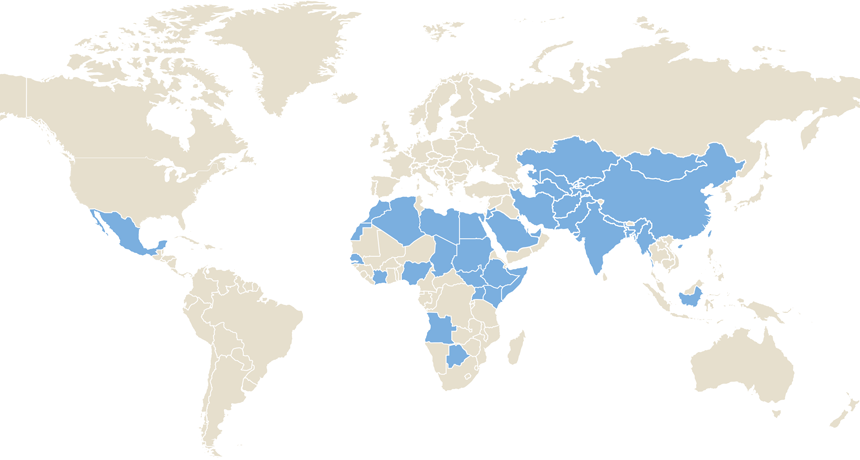

TRANSMISSION RISK A vaccine offers long-lasting protection against hepatitis E, new research shows. The virus can spread when drinking water gets contaminated due to poor sanitation. Shaded areas denote countries where waterborne hepatitis E remains a health problem.

redmal/iStockphoto, adapted by E. Otwell; source: WHO

A vaccine against hepatitis E shows potent, long-lasting protection against the virus. The finding from a huge study in China could clear the way for other countries to adopt the shots against hepatitis E, which is most commonly spread through tainted water.

“I consider this to be extremely important for the field,” says Heiner Wedemeyer, a physician and hepatitis researcher at Hanover Medical School in Germany. “This is a largely underestimated global health burden.” The vaccine fills a void, he says, because no other candidate vaccine aimed at this virus is anywhere near approval.

People get infected by hepatitis E by drinking contaminated water or eating undercooked meats or shellfish. Symptoms include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, fever, jaundice and liver failure. The World Health Organization estimates that the virus infects 20 million people each year. Of those, more than 3 million have acute cases and 56,600 die. Hepatitis E can be especially dangerous for pregnant women. In Bangladesh, the virus kills 1,000 pregnant women a year, estimates show.

To test the vaccine’s long-term effectiveness, 112,604 people ages 16 to 65 were randomly assigned to get either three shots of the vaccine over six months or three shots of a hepatitis B vaccine, as a control group. About 4½ years after finishing the vaccinations, seven people who got the hepatitis E shots had contracted hepatitis E, compared with 53 in the control group. The results suggest that antibodies to the vaccine were 87 percent protective, researchers report in the March 5 New England Journal of Medicine.

The number of infections was low overall because China has little waterborne hepatitis E due to improved sanitation. Most infections in the study region arise from the type of hepatitis E found in tainted pork. There are four known types of hepatitis E , some waterborne and some in food. The vaccine probably protects against all four, says study coauthor Ning-Shao Xia, a molecular biologist at Xiamen University in China.

The vaccine comprises particles of the hepatitis E virus that trigger an immune reaction but cannot cause infection or mutate back to a virulent state. China approved this vaccine in December 2011 based on early results from this trial and has geared up a manufacturing apparatus for it. Xia says that countries with recurrent waterborne epidemics of hepatitis E “should step forward to evaluate, approve and purchase the vaccine.” Such outbreaks have recently hit South Sudan and Darfur and are recurrent problems in India, Nepal and Bangladesh.

Jay Hoofnagle, a physician who oversees liver disease research at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases in Bethesda, Md., says the waterborne types of hepatitis E virus pose the greatest risk because they spread rapidly in populated areas with poor sanitation. The new study provides “fairly convincing” data that this vaccine would prove effective in such settings, he says. “You could move into an epidemic and start vaccinating everybody in sight to contain the outbreak.”

“In refugee camps,” Wedemeyer adds, “it would be unethical not to provide the vaccine at this stage.” Such emergency uses might clarify whether the vaccine can halt the spread of the virus, which occurs when feces from an infected person enters the water supply. Such deployment might also show whether the vaccine works in children and immune-compromised people.

The vaccine is called Hecolin and is made by Xiamen Innovax Biotech Co. It’s currently sold on the private market in China, Xia says. Another vaccine tested by GlaxoSmithKline also showed promise but was later abandoned for business reasons (SN: 3/3/07, p. 131).