Ancient oceans’ top predator was gentle filter feeder

Fossils suggest distant lobster relative used bristled limbs to net prey, not spike it

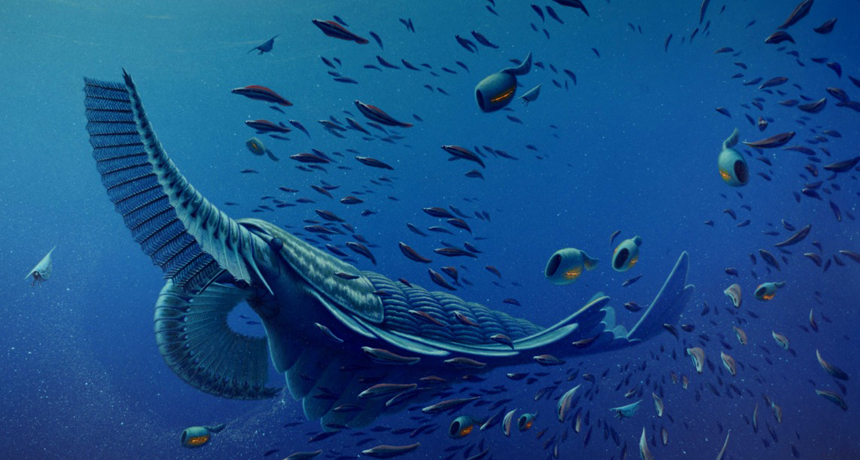

GENTLE GIANT Tamisiocaris borealis, an up to 70-centimeter-long filter feeder from the Cambrian period, swims among other ancient species in an artist’s reconstruction. The giant predator probably used its spiny appendages (left) to sweep food into its mouth, scientists say.

Robert Nicholls/Paleocreations