3-D printing builds bacterial metropolises

Technique may help researchers study antibiotic resistance

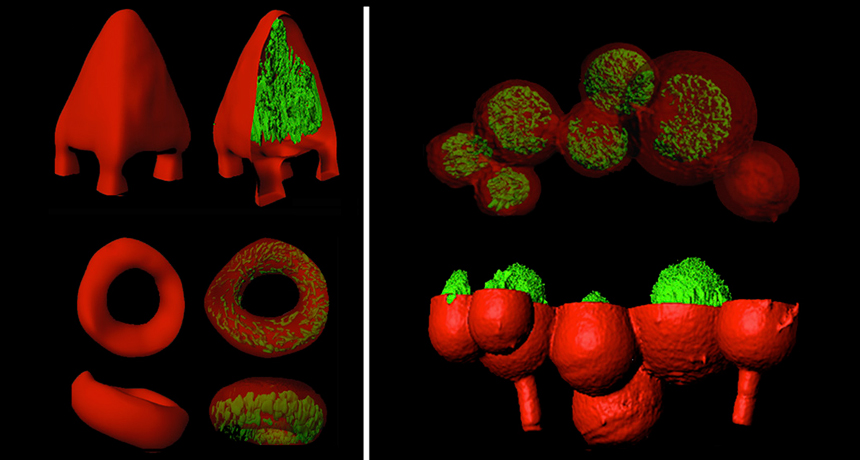

CAGED IN Colonies of bacteria (green) nestle inside 3-D printed gelatin shells (red) in this computer-assisted 3-D microscopy image. Researchers can use 3-D printing to simulate social interactions between microorganisms.

J.L. CONNELL ET AL/ PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES 2013