Chock-full of unicorn horns (narwhal teeth), griffin claws (antelope antlers), leopard skins, petrified wood or other gems hand-picked from nature, “cabinets of curiosities” have developed a modern-day reputation as whimsical caboodles of miscellaneous oddities. This book will overturn that impression. A proper collection was “a model of universal nature, made private,” as Francis Bacon, the 17th century philosopher and statesman, is quoted as saying.

In providing a grand tour of Western European collections, Arthur MacGregor shows that “purposeful collecting” embodied nothing less than revolutionary thought on cosmology and nature. MacGregor, a curator at the AshmoleanMuseum in England, pays special attention to the changes in organization, preservation and interpretations of insects, birds, shells, gems and other natural items between the Renaissance and the Enlightenment.

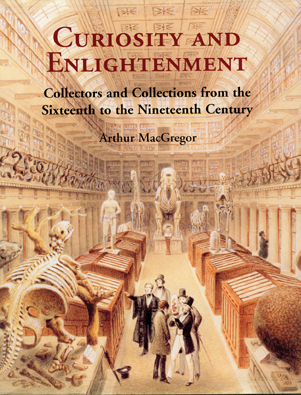

The collections often evolved into public museums, and their popularity led to creative innovations in preservation and presentation techniques. How, for example, should the life cycle of a tree be displayed, or the anatomical lessons of a corpse tastefully exposed?

By the mid-1700s museum collections of the animal world were being reorganized according to Linnaeus’ rankings, and anatomical collections were incorporated into medical schools. With each illustration and description — a perfect glass flower, wax heart, scrutinized fossil or embryo placed according to its similarity to another kind of animal embryo — MacGregor tells a tale of how modern science began.

Yale University Press, 2007, 386 p., $75.