An exotic quantum state that had previously appeared only under conditions of astonishing cold has made its room-temperature debut, reports an international team of scientists. In related experiments, other researchers have produced a similar state in different, still-chilly materials but claim that their experiments will lead to room-temperature versions as well.

The new findings, unveiled in independent reports in the Sept. 28 Nature, reveal a bizarre new branch of an already exotic family of quantum states of matter known as Bose-Einstein condensates.

Previously produced Bose-Einstein condensates, which form only at temperatures near absolute zero, include a superfluid of liquid helium that flows with no friction (SN: 2/26/05, p. 142: Available to subscribers at A quantum fluid pipes up) and condensates of dilute gases (SN: 1/17/04, p. 35: Available to subscribers at A Solid Like No Other: Frigid, solid helium streams like a liquid). Superconductors, which are materials that permit electric current to flow without resistance at ultracold temperatures (SN: 4/1/06, p. 196: Cool Wire: Nanostructure boosts superconductor), exhibit many of the properties of Bose-Einstein condensates, but physicists disagree on whether those materials precisely fit the condensate’s definition.

The newest findings might make quantum-physics experiments easier by eliminating tricky cryogenics and might lead to practical payoffs such as extremely low-power lasers. The two new demonstrations also buoy scientists’ expectations that they’ll someday find a way to dramatically raise the temperatures required for superconductor operation—an achievement that could lead to enormous energy savings.

Room-temperature superconductivity is “definitely at the back of people’s minds,” notes David Snoke, a University of Pittsburgh physicist who also does research on novel Bose-Einstein condensates (http://blogs.nature.com/nature/peerreview/trial/). However, he adds, the means to achieve such superconductivity remain unclear.

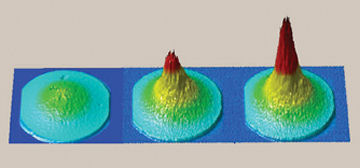

Bose-Einstein condensates typically form when falling temperatures induce the atoms of a gas or other particles to exhibit their wavelike quantum nature and grow larger, as dictated by Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle. The expanding waves then overlap and meld into, in essence, a single object—the condensate.

In both the new reports, however, the experimenters used means other than extreme cold to make the condensates. The starting materials, which had not previously been formed into condensates, were what physicists call quasiparticles. According to Sergej O. Demokritov of the University of Münster in Germany, quasiparticles are ephemeral energy excitations that come and go inside solid materials, somewhat like the crests of waves in an ocean do. Quasiparticles can collide and exchange velocity as billiard balls do and otherwise behave fleetingly like standard particles, he notes.

In the set of experiments conducted at room temperature, Demokritov and his colleagues zapped a thin film of the magnetic compound yttrium iron garnet that they had placed in a device akin to a microwave oven. The treatment boosted the film’s population of quasiparticles known as magnons.

In the other, much lower-temperature experiments, physicist Benoît Deveaud-Plédran of the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland and his colleagues fired a laser at a microstructure made of the semiconductor cadmium telluride. In the material, the procedure produced quasiparticles called exciton polaritons, which form when photons of light and electrons collide.

In each experimental run, the elevated quasiparticle densities caused the wavelike entities to overlap and form condensates, the investigators say.

In a commentary published with the reports, Snoke says that the magnon-making study, while promising, lacks firm evidence that the magnetic waves exactly match each other as they should in a condensate.

Demokritov says that in additional experiments, his team has demonstrated that the waves match.